The Last Line of Defence: Why Organic Winegrowers Are Desperate to Save Copper

France’s new restrictions could strip organic vineyards of their only reliable shield against disease.

When storms sweep through a vineyard in midsummer, the air fills with that sharp metallic scent of rain striking soil. For organic winegrowers, it’s also the scent of dread. Every rainfall brings renewed pressure from mildew; a fungal adversary that can strip a crop bare in a matter of days. And this year, many of those growers feel dangerously under-equipped to fight back.

This summer, France’s health and environmental agency, ANSES, introduced new restrictions on copper use in agriculture, tightening the dosage, frequency, and conditions of spraying. For organic producers, who depend on copper as one of their few legally approved defences against fungal disease, the decision feels less like a fine-tuning of regulation and more like the loss of their last line of defence.

Although the change technically came into force months ago, the outcry has intensified in recent weeks as growers are now confronting its real-world consequences: popular copper formulations have disappeared from the market, new label restrictions are being enforced, and the timing collides with one of the most disease-prone phases of the growing season. What was once an abstract regulatory update has suddenly become an existential problem in the vineyard.

Who is ANSES?

ANSES, the Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail, is France’s public body responsible for assessing health and environmental risks. It regulates pesticides, food safety, and workplace exposures, operating under both the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture.

In July 2025, ANSES renewed the authorisation of copper-based fungicides for crops such as vines, potatoes, and apples, but imposed stricter limits to protect workers and reduce contamination of water and soil. Copper is now officially classified in Europe as a “candidate for substitution” under Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009, meaning regulators actively encourage the search for safer alternatives.

For organic winegrowers, that substitute doesn’t yet exist.

Why organic farmers rely on copper

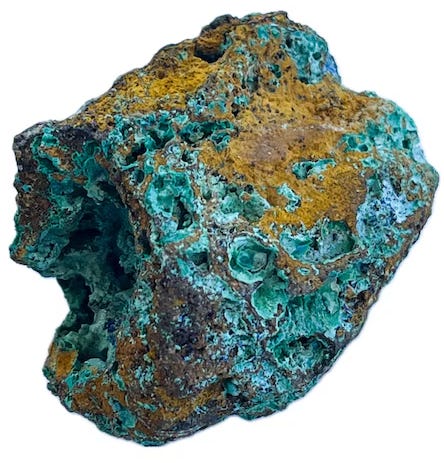

To understand the current alarm, it helps to know the chemistry behind this bluish mineral that has coloured vineyard barrels and sprayers since the late 1800s.

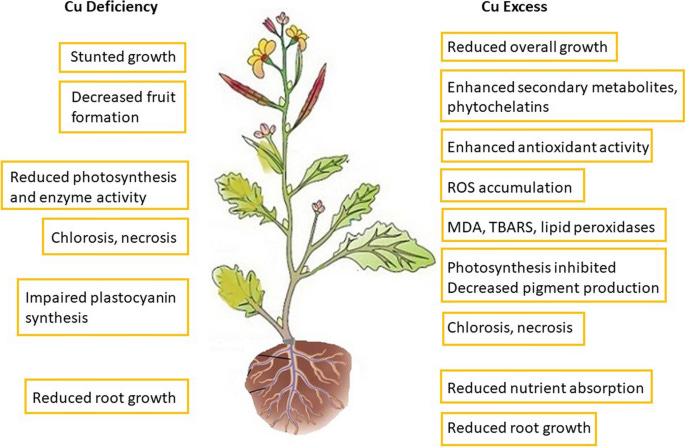

Copper (usually in the form of copper sulphate, copper hydroxide, or copper oxychloride) acts as a broad-spectrum fungicide and bactericide. When sprayed on leaves, it creates a thin film of positively charged copper ions. Those ions disrupt key enzymes within fungal spores, effectively killing or disabling them before they can infect the plant.

Unlike many synthetic fungicides that target a single metabolic pathway, copper has a multi-site mode of action, which makes it difficult for fungi to develop resistance. That’s part of its enduring value: after more than a century of use, no fungal population has evolved total resistance to copper.

It’s also one of the few compounds that is naturally occurring, meaning it can be used in organic farming… a crucial distinction. While “organic” prohibits synthetic chemical pesticides, it still allows certain natural minerals and biological agents, provided they meet strict environmental and toxicological criteria. Copper is one of those rare exceptions.

How copper differs from synthetic pesticides and why organic growers still defend it

1. Broad, resistance-proof protection

Synthetic fungicides usually target a single enzyme or pathway, which makes them effective but easy for fungi to resist. Copper attacks on multiple fronts (disrupting enzymes, cell membranes, and respiration) which is why no fungal strain has ever developed resistance to it.

2. Naturally occurring

Copper is a mineral found in nature and even essential in small doses for plants and animals. Synthetic pesticides are lab-made molecules designed for precision, not persistence. Copper’s natural origin allows its use in organic farming, though that same persistence in soil is what worries regulators.

3. Little to no residue in wine

Used correctly, copper stays on leaves and soil rather than penetrating grapes, leaving almost no detectable residue in the finished wine. Synthetic products, even when safe, can leave traces that conflict with organic certification standards.

4. Fits the organic mindset

Copper prevents disease rather than curing it, reflecting organic farming’s focus on prevention, timing, and minimal intervention over chemical correction.

Still, copper is no perfect solution. It accumulates in soil and can harm earthworms and microbes if overused. Many synthetics eventually break down, while copper does not. Growers defend it not because it’s ideal, but because it’s the only tool that still works within both organic rules and reality.

A brief history: from the Bordeaux mixture to modern organics

Copper’s role in viticulture dates to the 1880s, when French scientist Pierre-Marie-Alexis Millardet noticed that vines sprayed with a blue concoction of copper sulphate and lime (known as the bouillie bordelaise or Bordeaux mixture) were mysteriously resistant to downy mildew. The discovery revolutionised plant protection and saved Europe’s vineyards from devastation.

Over the decades, copper became the cornerstone of fungal disease management. Even today, that same blue mixture remains the primary tool against downy mildew in organic vineyards from Champagne to Burgundy to Bordeaux.

Yet copper’s effectiveness comes at a cost: it does not degrade. Every treatment leaves behind residues that accumulate in the soil, gradually raising copper levels to potentially toxic concentrations for earthworms, microorganisms, and even the vines themselves. In old European vineyards, soil copper levels as high as 300–500 mg/kg have been recorded — several times higher than natural background levels.

What organic regulations currently allow

Under European Union organic farming regulations, copper use is capped at 6 kg of elemental copper per hectare per year, averaged over seven years. That rolling average was designed to help growers adapt to variable conditions (ie applying more in humid years and less in dry ones).

But under the new ANSES framework, those national adjustments have been tightened. Most products have been withdrawn from the market because manufacturers failed to supply the required new safety studies. Only two copper-based formulations were reapproved with usage conditions that many growers argue are not realistic in the field.

The authorised rate now allows applications roughly equivalent to 400 g of copper per hectare every seven days. In a year of repeated rainfall or storm cycles, that interval may be far too long to protect vines effectively.

The copper expert for the Fédération nationale d’agriculture biologique (FNAB) has outlined that, in organic viticulture, effective protection can sometimes require treatments as frequently as every three days during stormy periods. Under the new rules, that level of responsiveness would no longer be possible, leaving vines vulnerable during the most critical infection windows.

Industry associations including the FNAB, France Vin Bio, and the CNAOC (National Confederation of Appellation Wine Producers) have urged the Ministry of Agriculture to grant temporary exemptions, allowing evening sprays during flowering and reinstating the ability to average copper doses over multiple years, a flexibility removed under the new system.

Why copper is being restricted now

From a regulatory perspective, the reasoning is clear: copper is both toxic and persistent. Though naturally occurring, it behaves differently from biological inputs: it doesn’t decompose, wash away harmlessly, or break down into inert forms. Instead, it accumulates in soil and sediments, where it can impair microbial life, alter nutrient cycling, and harm aquatic ecosystems through runoff.

Workers handling concentrated copper solutions are also at risk of skin irritation and inhalation exposure, especially when spraying under windy conditions.

As ANSES stated in its July report, the renewed authorisations come with “measures to limit exposure of workers and contamination of water and soils.” The agency emphasised that its decisions were based on protecting public health and the environment, not on undermining organic production.

But for many farmers, it feels like the balance has tipped too far toward precaution without providing viable alternatives.

The mildew menace: a changing climate, a narrowing toolbox

At the heart of this debate lies one stubborn adversary: downy mildew, a microscopic fungus-like pathogen that thrives in warm, humid conditions. Its scientific name, Plasmopara viticola, gives away its preference for vines. Once established, it can devastate yields and destroy a vintage’s quality.

The disease first struck Europe in the late 19th century, carried from North America along with phylloxera. It infects young leaves, shoots, and clusters, leaving behind the telltale oily yellow spots that later turn brown and necrotic. When humidity rises, a white cotton-like growth appears. A sign that spores are multiplying and spreading.

Climate change has made this enemy far more aggressive. Rising temperatures extend the growing season, while erratic rainfall and frequent storms create perfect conditions for fungal proliferation. Mildew that once appeared sporadically now returns several times per season. Some Champagne growers reported record infection pressure during the wet summers of 2021 and 2024.

Conventional viticulture can rotate through synthetic fungicides with different active ingredients. But organic growers are limited to copper and sulphur. Sulphur, while effective against powdery mildew, is useless against downy mildew. Without copper, organic vines are effectively defenceless.

A difficult balance between protection and preservation

No one disputes the environmental impact of copper. Scientists have documented soil organisms’ sensitivity to long-term accumulation. Some biodynamic and regenerative growers have already reduced their copper use below 3 kg/ha annually, supplementing with canopy management, resistant grape varieties, and plant-based sprays.

But those techniques are not universally applicable. In regions like Champagne, where vines are densely planted and rain can linger under the canopy, mildew can spread in days. If treatments fail, growers lose both yield and certification, the foundation of their livelihood.

Industry representatives stress that the wine sector has invested heavily in the ecological transition, yet for now copper remains the only truly effective line of defence against downy mildew.

What’s next?

France’s organic sector has called for new toxicological studies that reflect real-world field conditions rather than laboratory exposure models. They argue that the safety data should consider how copper is actually used (lower concentrations, finer sprays, and limited contact periods) instead of theoretical maximum doses.

In parallel, researchers are racing to develop biocontrol agents, microbial competitors, and disease-resistant grape varieties. Some INRAE projects have shown promise, but none yet offer the reliability of copper under severe mildew pressure.

For now, organic viticulture faces an uncomfortable truth: its most dependable defence is also its most politically vulnerable.

The broader question and looking ahead

This is not just a story about one molecule. It is a question of balance between idealism and pragmatism in sustainable agriculture.

Reducing environmental impact is essential, but so is protecting crops and livelihoods. Finding that balance requires nuanced regulation, transparent science, and time. Those are luxuries farmers rarely have during a stormy growing season.

The 2025 harvest may be behind us, but the debate is far from settled. As new data emerge and the effects of ANSES’s restrictions ripple through the countryside, pressure is mounting on regulators and researchers to find workable alternatives. The next growing season will arrive sooner than anyone expects, and the same question will return with the spring: how do I save my vines today?

For now, the answer remains blue, the faint sheen of copper on a leaf marking a fragile line between sustainability and survival.